Data sources and study population

Data for this study were obtained by linking different Swedish population-based registers using personal identity numbers [26]: the Total Population Register contains information about all individuals living in Sweden since 1968 [27]; the Medical Birth Register includes information on all deliveries in Sweden since 1973 [27]; the Swedish National Patient Register (NPR) covers more than 99% of somatic and psychiatric in-patient care records since 1987 and out-patient records from specialist health care since 2001 [28]; the Prescribed Drug Register (PDR) covers all filled drug prescriptions from 2005 onwards [29]; the Longitudinal Integrated Database for Health Insurance and Labor Market Studies (LISA) was established in 1990 and contains information on socioeconomic factors such as education, income, employment and occupation [30]; information on convictions comes from the National Crime Register (Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention); and the Multi-Generation Register links different generations through the personal identity number [27].

Using these registers, we identified all individuals born in Sweden between 1 January 1990 (due to information availability from LISA) and 31 December 2009 (n = 2,042,257) as well as their parents and followed them until 31 December 2013. We excluded individuals who were stillborn or had major congenital malformations, twins, everyone who died or migrated during the first year of life, and individuals with missing information on their own or their parents’ personal identity number. After exclusion, the analytical sample consisted of 1,877,901 individuals. Among these, we identified subgroups of full siblings (1,271,883 individuals from 568,058 families) for the sibling comparison, half-siblings (304,881 individuals from 132,699 families) and full cousins (1,466,630 individuals from 597,317 families).

Several studies have used Rutter´s index of psychosocial adversity or its adapted version to assess the association with ADHD [8,9,10]. We used information from seven specific psychosocial adversities to create an index of cumulative psychosocial adversity in the family during the child’s first year of life. This index uses the available register data to approximate Rutter´s index [9], and has been used in previous studies as well. We considered the following dichotomous psychosocial adversity factors:

Parental bereavement, defined as any loss of first-degree relatives of the child´s parents (parents, partner, child, siblings) during the child’s first year of life, based on the Total Population Register.

Parental divorce during the child’s first year of life, defined as “yes” if the family situation has changed based on information from LISA the same year.

Parental financial problems during the child’s first year of life, defined as “yes” if the family had low economic status, based on information from LISA the same year. Low economic standard was defined as a household disposable income of less than 60% of the median income in the whole population in that particular year [31].

Parental low education during the child´s first year of life, defined as “yes” if at least one parent’s highest achieved educational level was less than 9 years of education, based on information from LISA the same year.

Any parental psychiatric history during child’s first year of life, based on ICD codes of parental neurodevelopmental and psychiatric conditions (Supplementary Table 1) identified from NPR the same year, versus none.

Any parental conviction for violent crime (e.g., homicide, assault, robbery, threats and violence against an officer, gross violation of a person’s integrity, unlawful coercion, unlawful threats, kidnaping, illegal confinement, arson, and intimidation) during the child´s first year of life, versus none. Data was obtained through the national Crime Register the same year.

Large family size, defined as 4 or more children in the family at the time of birth of the index person, based on information from the Medical Birth and Multi-Generation Registers.

All above mentioned psychosocial adversity factors were summarized into a cumulative psychosocial adversity index that was used as exposure, varying from 0 to 7. In the analysis, we treated this index as both a continuous and categorical variable, thus both assuming a linear dose-response pattern and allowing for deviations from linearity. Since few individuals were exposed to 4 or more factors (1293 exposed to 4 factors; 18 exposed to 5 factors; and no one was exposed to more than 5 factors) we merged these categories, resulting in index categories of 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4 or more factors for the categorical analysis.

The outcome variables were defined as diagnosis of ADHD or autism after the age of 3 based on ICD-9 and ICD-10 in the NPR (Supplementary Table 2). Moreover, individuals with ADHD were also identified through PDR by Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) (Supplementary Table 2) codes for ADHD medication. Both ADHD and autism were analyzed as time-to-event outcomes.

We included parental age at child’s birth, child’s year of birth, and parent’s country of origin (Nordic, European, non-European) as covariates and adjusted for them in the analyses.

Statistical analysis

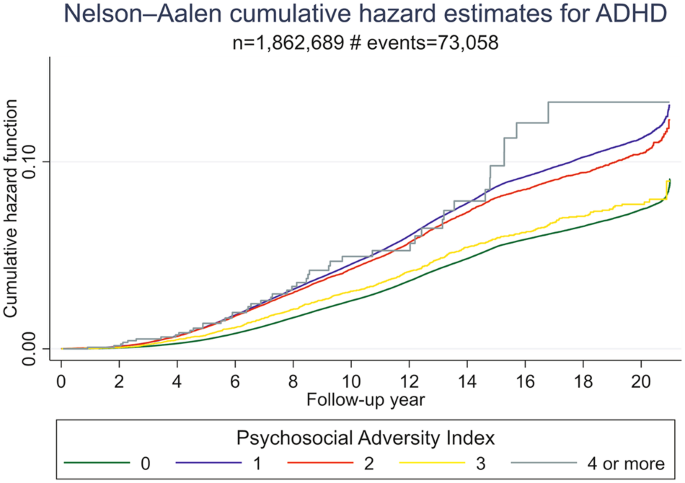

The associations between cumulative psychosocial adversity and ADHD and autism were assessed with hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI), using Cox regression. The children were followed from age 3 (baseline) until migration, death, end of follow up (December 31, 2013) or a diagnosis of ADHD/autism, whichever occurred first. Separate analyses were conducted for ADHD and autism, and for psychosocial adversity as continuous and categorical variables. We used Nelson–Aalen curves to visualize the probability of the outcome at a time interval between different levels of the cumulative exposure. First, the analyses for crude and adjusted models were conducted at a population level. Cluster robust standard errors were used in these analyses to account for dependence between individuals in the same family in the whole population. To adjust for unmeasured familial confounding, we repeated the analysis in different groups of relatives: full siblings who share 50% of their genes and all of their shared environment, half-siblings with 25% of shared genes and partly environment and full cousins with 12.5% shared genes and some of their environment [18]. In these analyses we used stratified Cox regression, where each group of relatives (e.g., each set of siblings) was entered as a separate stratum into the model grouped by the family identification code. Conceptually, the stratified Cox regression compares the risk of the outcome for individuals with different exposure levels within (i.e., stratifying on) the same group of relatives. By virtue of the stratification of groups of relatives, all factors that are constant within these groups (e.g., parental genetic make-up for full siblings) are automatically adjusted for. In the supplementary material (Supplementary Table 3), we provide the number of strata for which there is variation in the exposure and at least one child developed the outcome; most of the information about within-stratum associations is derived from these strata.

Sensitivity analyses

To investigate if the effect of exposure to psychosocial adversity on ADHD was modified by autism, we fitted a model where ADHD was the outcome and autism was treated as a time-varying covariate, by including an interaction term between autism and the exposure in the model. Conversely, to investigate if the effect of exposure to psychosocial adversity on autism was modified by ADHD, we fitted a model where autism was the outcome and ADHD was treated as a time-varying covariate and included an interaction term in this model between ADHD and the exposure. In both these models we only used the continuous measure of psychosocial adversity.

To account for diagnostic uncertainty, we reran the analyses after having redefined the outcome: only those individuals diagnosed with ADHD or autism at least twice were considered as diagnosed, while individuals with one diagnosis were considered as undiagnosed. We also performed sex-stratified Cox regression on the general population to assess differences between boys and girls. Furthermore, in order to repeat the analysis among individuals with complete follow up from 2001, when information from both outpatient and inpatient care was available, we restricted the analysis to individuals turning 3 in 2001 or later (i.e., those who were born 1998 and onwards). Data management was performed in SAS software (Version 9.4 of the SAS System for Windows. Copyright © [2021] SAS Institute Inc). Analysis was performed in Stata (StataCorp. 2019. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.). This study was approved by Stockholm’s Regional Ethical Review Board (Dnr 2013/862–31/5). Code availability: see supplementary materials.

This content was originally published here.