“If you’ve ever been on a night out where you got blackout drunk and have laughed the next day as your friends tell you all the stupid stuff you said, that’s what being autistic feels like for me: one long blackout night of drinking, except there’s no socially sanctioned excuse for your gaffes and no one is laughing.”

When my eyes first scanned this sentence, I got chills. A tiny new window of understanding suddenly creaked open in my mind. Not because I spend my weekends throwing back liters of Absolut, but rather because I immediately recognized what the author of these lines, Fern Brady, meant: that anxious dread within social situations, of not quite knowing or understanding what you have done wrong, and the worry about how on earth to fix it. Who among us hasn’t experienced this feeling?

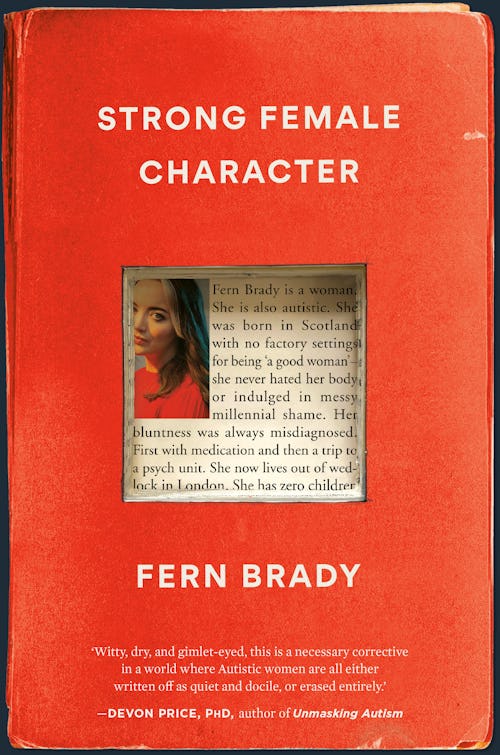

Of course what Brady is talking about isn’t really like ordinary social anxiety at all. I know this because my son, like Brady, is autistic, and I have an inkling of how incredibly strange the world and its social customs sometimes seem to him. Brady’s eye-opening, whip-smart new memoir Strong Female Character is an extraordinary guide to the challenges the neurodivergent face in the neurotypical world.

“So much of describing the experience of being autistic is about interiority, about having this huge inner life and sensory experiences that you can’t articulate to most people.”

If you aren’t familiar with Brady, it’s probably because you’re not from the United Kingdom. Over there, she is well-known for her scathingly witty stand-up and for her appearances on popular British chat shows. She has been a regular on Taskmaster, a delightfully goofy panel show in which a group of comedians is given a list of bizarre tasks to complete (i.e., paint a self portrait on a toilet seat using only a sausage). Strong Female Character is a bestseller in the United Kingdom, and was released in the United States last month.

Brady was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in 2021, at the age of 34. Her Twitter post about it was typical of her style — both no holds barred and wryly funny: “Got autism diagnosis this week. Told my dad, who responded by asking me what I had for dinner tonight. I guess this saves me working out which parent has it.”

Given that she has an audience on both TV and for her stand-up (the show she’s currently touring is called Autistic Bikini Queen), I asked Brady recently why she chose to write a book as well. “If I were to speak about my autism on stage, I have to describe it in terms most people understand, like mention my social awkwardness and how it impacts those around me when in reality that’s the last thing I want to talk about when I speak about autism,” she told me in an email.

“So much of describing the experience of being autistic is about interiority, about having this huge inner life and sensory experiences that you can’t articulate to most people. It felt like a book was the best place for that. I also feel I communicate more fluently when writing, so there’s that. And I’d noticed in the past that people seemed to treat me with more respect when they read my writing, which made me realize most people who speak with me in person think I’m stupid. This isn’t me projecting an insecurity — there’s great research on how non-autistic people consistently misjudge autistic people as less intelligent than them. I’ve realized that neurotypicals value the manner in which you say stuff, rather than the content of what you’re actually saying, so in that regard performing stand up as a working class Scottish woman with a weird voice can be quite limiting for me.”

Brady’s memoir covers a lot of autism ground. She talks about the stress and exhaustion of masking, which is when an autistic person learns how to perform certain socially acceptable behaviors such as holding eye contact, and to hide autistic behaviors like stimming, in order to better fit in. She explains why we need to do away with the unhelpful idea that we’re all kind of somewhere on the spectrum. (“No one is a little bit autistic,” she writes. “You’re autistic or you’re not. The spectrum describes your support needs.”) She talks about the failure of the medical establishment to properly diagnose girls and how she herself was once told by a doctor that she didn’t fit the criteria because she made eye contact and had a boyfriend.

Now that she’s so open about her autism, I wondered if she’s felt less pressure to mask. “Not really,” she wrote back. “My understanding of autism has changed massively, but that doesn’t mean most other people aren’t still as clueless as ever. I did cautiously unmask in some situations (e.g., doodled during meetings instead of forcing myself to make eye contact to help me concentrate on what others were saying), but it just meant the neurotypicals I was meeting with asked if I was listening. Sometimes I get the courage to ask for lighting to be turned down in certain work environments, but I just find it so embarrassing asking for the tiniest adaptations because I know non-autistic people will view it as me being precious or difficult to work with. I’m sorry I can’t tie it up in a bow and give you a more optimistic answer!”

Brady’s blunt candor, and reluctance to sugarcoat the realities of life with autism is no small part of what I loved about her book. She writes movingly about having meltdowns, explaining that despite their physical intensity, meltdowns are not, as people often assume, about anger. Meltdowns are in fact expressions of extreme anxiety, and Brady describes her own experience of them in great detail: what they feel like, what triggers them, how she has torn her own kitchen cabinets off their hinges. And it’s there, in those details, that Brady really brings home what her experience of the world has been as an autistic woman.

“I’ve realized that neurotypicals value the manner in which you say stuff, rather than the content of what you’re actually saying.”

She writes about growing up in Bathgate, Scotland, with parents who were alternately perplexed and infuriated by her interests and routines, and who often labeled her as “evil.” She describes a childhood so filled with loneliness she once befriended a tree. She details her experiences with self-harm and how as a teen she once tried to carve “F*ck” into her leg. (It later healed in such a way that she spent two weeks “with the much cheerier ‘A-OK’” taunting her every time she changed clothes.) Brady eventually managed to get out of Bathgate to attend the University of Edinburgh but describes how she struggled to make sense of many of the basics of university life, like how to actually turn in an essay.

Brady also writes about her bisexuality and how her lack of regard for social norms made her confident in her queerness, until society told her otherwise. (“It took repeated messages, over and over and over again, to instill a suitable amount of shame in me.”)

Later, she details the trauma of escaping an abusive boyfriend and gives a vivid account of working as a stripper, a job she says suited her particular sensibilities. “Of course I enjoyed a job that was highly tolerant of weirdos, almost impossible to get sacked from, had none of the fluorescent lighting that made most offices or supermarkets jobs overwhelming, involved the same routine night after night and the same dumb conversations with men with no tricky social cues to read.”

During our email correspondence, I asked her whether being open about her autism has changed her life. “I still go back and forth on thinking I can learn how to be socially great,” she told me. “The best thing about telling people I’m autistic is I met loads of cool autistic people and [was] able to connect with them on a level that I struggle to with most other people. So I now feel like I have a little network of people I can lean on a bit when I have autism-specific questions. I also feel like the book has had way more impact than anything I’ve ever done in comedy, which has been lovely.”

But Brady makes it clear that “coming out” about her diagnosis hasn’t necessarily curbed people’s assumptions about her intelligence or capabilities. “There has been almost no benefit in telling neurotypical people about my autism, as it’s perceived very negatively by a lot of them,” she told me. “I feel a constant clash between my massive ambition in comedy versus wanting to talk about autism and improve people’s understanding around it.”

“No one is a little bit autistic. You’re autistic or you’re not. The spectrum describes your support needs.”

Despite this tension, Brady doesn’t have any plans to stop talking about it. I recently stumbled across a very funny clip of her on the British chat show The Last Leg in which she talks about how neurotypical people will often try and “smooth over” news of her autism by reassuring her it’s a superpower. “A superpower?” she said. “Really? Is it? Would it have made a good film if instead of having superhuman strength and being able to fly around the world on a whim, that Superman instead monologued at you about the 1960s poet Sylvia Plath, at length, with no ability to register your disinterest?”

It’s a joke, obviously, but her point is that the whole “superpower” idea isn’t particularly helpful to the autistic community, just as the platitude that everyone is “somewhere on the spectrum” mostly does a disservice to people dealing with the very real challenges of autism.

After reading her book, it isn’t Brady’s autism that feels like a superpower to me. Rather, it’s her ability to share, with such bold honesty and tremendous heart, her experience. In so fearlessly telling her story, she exposes the many ways in which society fails the neurodivergent, and invites readers to think about what a better world might look like. She raises an unapologetic boot, and artfully kicks open that window of understanding just that much more.

This content was originally published here.